Description

Planning for evaluation while you design and implement your program – rather than at the end of your program – enables you to adjust your program midstream or at any point in the process as needed, focus on better strategies, know what revisions to make, and enhance early program successes. To build evaluation plans into your efforts to engage contractors as partners, identify key data points to track before launching your demand creation efforts. This will support your overall program evaluation and data collection plan.

You should consider evaluating the effectiveness of your contractor engagement and workforce development strategies. This handbook provides guidance and resources to help you:

- Establish metrics and qualitative evaluation questions based on goals and objectives

- Design measurement strategies and a process and schedule for data review and assessment

- Design an approach for managing and sharing data internally and with partners

- Integrate these metrics and strategies into your overall evaluation plan.

To ensure that your program is making progress towards your contractor and workforce goals and objectives, evaluate and adapt as often as necessary as you recruit contractors and develop your workforce, applying lessons learned to improve program performance.

Step by Step

Consider how to measure progress before you implement your contractor engagement and workforce development activities.

To design an evaluation plan, identify the key components needed to measure progress toward your contractor and workforce objectives. This will support your program’s overall data collection and evaluation plan.

While evaluation approaches will vary based on your organization’s metrics and reporting requirements, there are four basic steps involved with planning to evaluate the contractor engagement and workforce development aspects of your program, as follows.

Evaluation of your contractor recruitment and development work is based on your contractor engagement and workforce development objectives. To understand the progress you make towards those objectives, identify what you will measure, how and when you will measure it, and who the audience is for the evaluation.

Sometimes the metrics to track progress are obvious and follow directly from the objectives (e.g., number of home energy upgrades completed). Other times, the objectives have an element of subjectivity or may not be precisely measurable (e.g., customer satisfaction); discuss these evaluations with contractors to gain their buy-in from the beginning. In these cases, you will need to determine what metrics to use as indicators of success and plan how to collect qualitative feedback on those objectives, such as through surveys of contractors and customers.

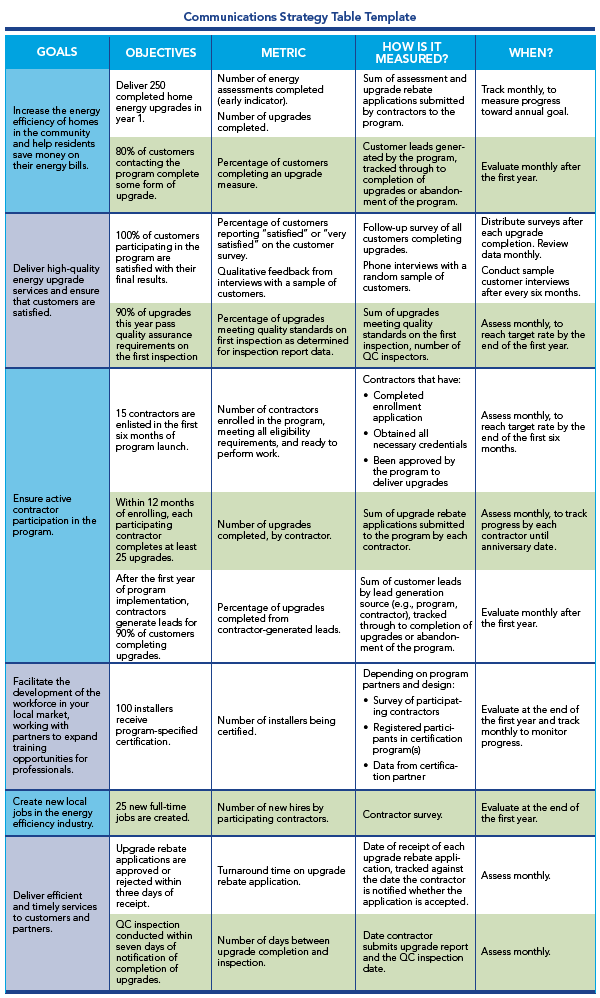

The following table contains examples of contractor engagement and workforce development objectives, as well as some metrics you might use to determine whether you’re meeting those objectives.

Identifying Qualitative Evaluation Questions

In the initial planning for process evaluation of your workforce development and contractor engagement, you should think about how you can collect qualitative data. Combining the qualitative and quantitative collection efforts can help minimize the burden on homeowners and contractors and reduce collection costs.

Consider asking contractors these questions to evaluate their experiences with the program and whether workforce development efforts are meeting marketplace needs:

- Did the program explain procedures to contractors in a way that was clear and easy to understand? Were program forms and applications easy to complete?

- Are there ways to improve data reporting processes between the contractor and the program?

- Did contractors have sufficient understanding of program incentives to accurately explain them to customers?

- Can the contractor-program interface be improved, from the contractor’s perspective?

- Are the program’s training and other workforce development opportunities relevant and helpful to contractor needs? Are they easy to take advantage of?

- Does the program’s training help students develop practical skills that they can use in the home performance industry? Has the training helped students find jobs?

- Do the communication channels the program has established, such as regular meetings, allow contractors sufficient opportunity to provide feedback and suggest improvements?

- Have contractors expanded their hiring of new employees or improved employee retention, due to participation in the program?

- Do contractors have additional comments on any aspect of their program experience?

Make it easy for contractors to provide answers to these questions by using an online survey or asking them at a group contractor meeting.

Customer feedback on contractors should also be a key component of your qualitative data gathering, as it is an important part of evaluating the overall customer experience. Consider including these questions in customer exit surveys post-upgrade in order to help you evaluate customer feedback on your contractors:

- Are customers satisfied with contractors’ work quality?

- Do customers feel that contractor communication was helpful in its timing, tone, and content, both during the assessment and during the upgrade work? Did contractors provide enough information for customers to feel informed about the process and comfortable about its progress?

- Did customers feel that incentives, the assessment, and the upgrade process were sufficiently explained to them?

- Did upgrades match customers’ expectations with regard to cost, timeliness, and estimated energy savings?

- Did contractors approach the customers’ home with professionalism and courtesy?

- Was the customers’ interaction with contractors overall a positive experience?

- Are there ways to improve the interface between contractors and customers?

Share customer feedback with individual contractors in order to help them understand how they can improve their performance. This subject is covered more fully in Assess and Improve Processes. The data you collect will also help you communicate the program’s successes and impact to stakeholders.

You will need a strategy for collecting and storing the necessary data over time to evaluate progress you’ve made on your goals and objectives. Your evaluation plan should indicate data you need to collect, how and when to collect the data (e.g., monthly reviews of upgrade rebate application submissions and response times, periodic customer and contractor surveys), the data collection process, and steps to check the data. Your contractor participation procedures and work flows should include requirements for data reporting on projects, including data about energy assessment results, energy upgrade measures installed, and anticipated energy savings. You will also develop reporting tools and forms that contractors and customers will complete, such as an upgrade rebate application, loan application, utility bill information release form and customer satisfaction survey.

When you defined your objectives, you set targets or milestones. Your evaluation plan should reflect this timing, so the data can be in place to help you measure your results and progress. The table in the step above provides examples of objectives with targets and the associated timing for collecting and reviewing data.

Some metrics will directly measure what you are interested in (e.g., number of energy upgrades can be determined based on upgrade rebate applications). For more complex metrics and qualitative feedback, you will need to track the measurements over time before being able to draw any initial conclusions. For example, measuring the program’s conversion rate from homeowner inquiries to energy upgrade completions will include a time lag, most commonly because of the steps in the upgrade processes and the customer decision-making process. Be careful when identifying, collecting, and tracking each metric and the data needed to calculate those metrics. Some of the data cannot be re-created retrospectively.

Gathering Data Through Targeted Sweeps in Michigan

Michigan Saves, formerly Better Buildings for Michigan, built a data-gathering and continuous learning process into its program delivery model. The program used a neighborhood “sweeps” model to target neighborhoods during limited timeframes with different marketing and outreach strategies, financing offerings, and incentives. During the sweeps, contractors dedicated whole crews for several weeks in each neighborhood to finish upgrades quickly and minimize disruption to homeowners. After sweeps ended, contractors continued to contact homeowners to encourage more upgrades.

Tracking and sharing results and lessons from these strategies in real time and after several sweeps allowed the program to test different methods and collect important data. The program used that information to evaluate the effectiveness of contractor engagement, marketing practices, and other strategies. Michigan Saves made changes after the initial sweeps to gather more real-time information to improve the effectiveness of the sweeps. They used this feedback to adjust in a timely manner how the program and contractors delivered the program. This mindset allowed the program to identify the more effective strategies for their different target audiences, focus resources on those strategies, and make significant progress towards their program goals.

Source: Spotlight on Michigan: Sweeping the State for Ultimate Success, U.S. Department of Energy, 2011.

As illustrated in the table in the previous step, you should determine not just what to measure, but how often you will review the data. You will track most of the metrics monthly (e.g., upgrade conversion rate, processing times for QA inspections, etc.); while others you will track annually (e.g., new hires, students certified). This review will allow you to determine whether the related elements of the program are on track and/or where adjustments might need to be made to improve your efforts. You may also want to develop a standard reporting format and produce a monthly report, which can be shared with participating contractors and other partners through your regular interactions with them.

As with all communications, the information you share and how you share it with contractors should be strategic so it can be most impactful. Present this information concisely and in conjunction with other regular communications, such as monthly coordination calls or quarterly participating contractor meetings. (See Developing Ongoing Coordination and Feedback Mechanisms.) You will also be communicating feedback regularly as part of ongoing process improvement efforts.

As part of your overall program design, you will have identified systems and tools that will support data collection and communication to both internal staff and external partners, stakeholders, and participants. You will want to ensure that the communication of your contractor engagement and workforce development results is integrated into the overall plan for communicating impacts.

Rutland County, Vermont Uses Ongoing Contractor Feedback and Performance Data to Improve Processes and Increase Contractor Conversion Rates

NeighborWorks of Western Vermont’s H.E.A.T. Squad actively engages contractors to collect data in order to improve processes and increase contractor conversion rates. The NeighborWorks H.E.A.T. Squad coordinator fosters ongoing communication with contractors and encourages emails, phone calls, and drop-ins. In addition to supporting direct communication, the program has monthly meetings with each participating contractor, during which staff collect key information to evaluate contractor engagement strategies. This personal contact helps make sure that contractor needs are being met in the program.

The program also conducts bi-monthly group contractor meetings as a forum to discuss any program issues or changes and as a learning opportunity for the contractors to share information with each other. The program shares contractor performance data monthly, including contractor conversion rates, and provides prizes for top performers, which motivates contractors to improve their results.

NeighborWorks’ strategy includes an emphasis on listening to contractors and collecting their feedback on issues with implementation, whether they relate to challenges with the customers in the field, the incentives and loan offerings, or with the program. This continual dialogue with contractors has facilitated NeighborWorks’ ability to improve its processes and also individual contractors’ business processes. Making efficient processing times a priority, NeighborWorks staff and participating contractors have worked to reduce the length of time for paperwork completion and upgrade conversions.

Source: Concierge Programs for Contractors – They’re Not Just for Consumers Anymore, Jonathan Cohen, U.S. Department of Energy; Ryan Clemmer, Enhabit; Melanie Paskevich, NeighborWorks; and Jay Karwoski, ICF International, 2012.

To avoid redundancy of data collection efforts and to look for ways that data collection can be streamlined to reduce costs and the burden on homeowners and contractors, take the additional step of reviewing this plan in the context of the broader program evaluation plan. You may find that other parts of the program will draw on some of the same data you have identified to meet evaluation needs. Plan to approach implementation of data collection for evaluation as a coordinated program.

Identify what types of data you are already collecting, and what types you may want to add to that existing data collection process. Contractors should ask some high-level customer feedback during their visits, so they can evaluate their performance in real-time and make adjustments; however, for more comprehensive evaluations, it is better for the program to follow up with customer surveys to collect feedback as part of your overall evaluation and data collection plan.

As you put together your evaluation plan, keep in mind your program’s evaluation budget and the costs associated with data collection activities, including staff time and outside vendors or consultants. To save on costs and time, leverage data that you are already collecting for other reasons (e.g., determine the number of participating contractors by counting enrollment), rather than create new processes. Then, be strategic about considering new polling, surveys, or interviews to address other information collection needs across all of your program’s goals. Establish a good data repository system that can adapt to changes in your program and your evaluation and data collection processes.

Tips for Success

In recent years, hundreds of communities have been working to promote home energy upgrades through programs such as the Better Buildings Neighborhood Program, Home Performance with ENERGY STAR, utility-sponsored programs, and others. The following tips present the top lessons these programs want to share related to this handbook. This list is not exhaustive.

A residential energy efficiency program’s success is dependent on the quality of work that contractors conduct in customers’ homes. Indeed, an in-depth examination of selected program strategies found that effective quality assurance and quality control programs provided a foundation for quality upgrades and were achieved through numerous program design and implementation decisions and follow-through. Many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners and Home Performance with ENERGY STAR Sponsors found that tiered and onsite quality assurance strategies, in addition to file reviews of upgrades reported to the program, worked well. Most programs use a tiered approach, in which a program inspects the first several upgrades completed by a new contractor and then inspects a specified percentage of subsequent projects. Onsite quality assurance is a useful strategy, both as a way of gathering feedback and as a training opportunity.

Programs conduct a broad range of verifications, including checking contractors’ certifications regularly, implementing a mechanism to re-check certifications, and verifying home performance professional safety skills (e.g., combustion training). In addition to inspections and feedback, some program also identified standards for ensuring quality work, including standards for technical work, for diagnostic tools and installed equipment, and for professionalism and customer service. Setting those expectations helped allow contractors to understand what was expected of them and better enabled them to help programs be successful from the beginning.

- In New York, NYSERDA uses a tiered approach for quality assurance. Inspection rates vary based on the contractor’s status in the program (see NYSERDA’s QA Procedures). The program inspects the first three projects that all contractors complete. After these initial projects, the program inspects 15% of a contractor’s completed projects, and at least one project annually. Customers may also request that field inspections be conducted within one year of the contractor’s work. If contractors have repeated QA/QC issues, NYSERDA increases the field inspection sampling rate, generally to 50% or more. If problems persist and are not resolved, NYSERDA sometimes suspends contractors from the program according to its QA procedures.

- The RePower program on Bainbridge Island, Washington, created a standardized process for quality control inspections. Energy upgrades completed under the RePower program could be randomly selected for quality control inspections, and were rated “Pass,” “Needs Minor Corrective Action,” or “Needs Major Corrective Action” based on the current RePower Weatherization Specifications Manual. If problems were found to require corrective action, contractors were required to perform the corrective actions at no additional cost to the customer. Repeated occurrences of an individual problem or serious problems resulted in a performance improvement plan or suspension from the RePower program. The program randomly selected 10% of their rebate applications for quality control inspection, and RePower staff worked to schedule an appointment with the homeowner within one week of selection.

- The NeighborWorks of Western Vermont program in Rutland County, Vermont, designed a quality assurance approach as a means to gather feedback and incentivize improvement. The program produced monthly contractor performance reports that compared contractor conversion rates, and then provided incentives to top performers. This approach was a productivity driver that encouraged contractors to make improvements to their business practices. During monthly one-on-one meetings, the program checked on each contractor’s client status list, made sure that no customers fell through the cracks, and gathered contractor feedback during the conversation. The program also set a timeline by which contractors must submit assessment reports to homeowners, with penalties in place for late reports. Using this approach, wait times dropped from four months to three weeks. See the Concierge Programs for Contractors webinar for more information. This approach has given contractors and the program the opportunity to improve over time.

- The Town of University Park, Maryland’s STEP-UP program worked to address variability in the quality of work that its contractors provided. The program approached this problem in two ways. First, STEP-UP issued a request for proposals for contractors that met specific performance benchmarks. From those proposals, the program then selected contractors with whom they had worked well in the past and began listing them as “preferred” contractors on their website. Ninety-nine percent of customers began selecting contractors from this list. Second, the program employed an energy coach for participating homeowners, to provide regular quality assurance of contractors’ work. The coach provided intermittent inspections at customers’ request, when they had concerns or when they chose to assist the program by allowing them to check on the contractors’ performance. The energy coach reviewed work proposals for scope and price; as a result, customers were reassured that they were getting the work they needed at a reasonable market price and therefore were getting fair value. By playing these roles, the coach gave customers assurance that they were receiving high value work from contractors and incentivized contractors to do quality work.

Many programs used the information they gathered through their quality assurance efforts to recognize contractors that deliver consistent, high-quality work. Rewarding good contractor performance can help you build trust, strengthen partnerships, and boost workforce morale. You can incentivize contractors to work for these awards by posting them on your website, announcing them at awards ceremonies or other events, recognizing them in newsletters, and encouraging contractors to post the awards on their websites.

- To improve contractor morale and work quality, electric utility Arizona Public Service (APS) and Home Performance with ENERGY STAR program sponsor FSL Home Improvements developed annual Contractor of the Year awards to recognize their top five participating contractors, given for the first time in early 2017. These contractors receive marketing benefits including a Contractor of the Year program logo for their website and additional marketing support. The program had been monitoring contractors’ work through quantitative metrics since 2012 and developed the quarterly scorecard as a tool to communicate contractor performance in 2016. These scorecards show how contractors compare to anonymized top and bottom scoring companies, based on their quality of measure installation, scope of work, customer satisfaction, and energy savings achieved. The program calculates each score based on performance over the past four quarters in an effort to avoid overly penalizing a contractor for any one insolated issue that they subsequently address. Not only do these scores enable annual contractor recognition, they also allow the program to give contractors regular feedback and increase contractor accountability. This comparative scoring has fostered friendly competition among contractors. The program has seen increased interest from contractors on how to improve their scores.

- Enhabit, formerly Clean Energy Works Oregon, singled out its contractors quarterly with honors such as the “James Brown Award” for the contractor with the most completed upgrades and the “Promoter Award” for showing the greatest job growth from one quarter to the next.

- The annual Charlottesville, Virginia, Local Energy Alliance Program (LEAP) “Blower Door Boss” award went to the contractor performing the most energy assessments while scoring the highest on customer surveys. The “Ruler of the Retrofits” title was bestowed on the company that scored the highest on customer feedback surveys and quality assurance reviews on home performance upgrades in Central Virginia.

- Maryland’s Be SMART program used awards and public recognition of accomplishments to help motivate home performance contractors that worked hard to realize significant energy savings. Be SMART gave awards to top performers that completed the most upgrades. The program presented awards for the greatest number of HVAC and home performance upgrades, the highest assessment-to-upgrade conversion rate, and the “Accuracy Award” for best rebate paperwork submission.

Early on, many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners focused on providing customers with a range of contractors to choose from, while providing contractors with access to customers. Customer feedback received by some programs, however, indicated that customers were confused or overwhelmed by the choices. A comprehensive evaluation of selected program strategies implemented by Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners found that programs were more successful when they provided customers with lists of pre-approved contractors; however, offering long lists of contractors without differentiating their products and services often led to inaction. To help customers distinguish between contractors and choose a qualified one, many programs provide customers with information about contractor skills, quality of past performance, proximity, and other factors. Some programs matched individual contractors directly with individual customers.

Customers can provide valuable information about the quality of contractors’ performance, and this feedback can supplement other information, such as field inspections, used to differentiate contractors based on their performance. Many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners incorporated customer ratings into the order in which they list contractors online, to help future customers select a contractor. Some programs also used rankings to evaluate contractors, support disciplinary actions, allocate benefits, and identify retraining needs. Through this approach, contractors had the opportunity to improve their standing and reap the rewards when customers saw that they could be relied on to do high-quality work.

- On Maryland’s Home Performance with ENERGY STAR website, homeowners can rate and review their contractors. Some contractors choose to reach out to their customers to encourage them to provide reviews. These customer reviews, along with contractors’ accreditations and services, are published on the website as part of each contractor’s information page. Users of the website can search for contractors and sort the results based on homeowner ratings and by geographical location. Users can also narrow their results according to which contractors participate in the customer’s local utility rebate program.

- Efficiency Maine provided customers with a “Find a Residential Registered Vendor” locator on its website. This locator listed the services each contractor offered, sorted the list by distance from the homeowner, and differentiated contractors based on number of projects completed and customer satisfaction. All contractors were added to the list when they met the program’s requirements. The list was sorted by location closest to the customer and number of completed projects, and also noted what services the contractor provides. The website also listed questions a homeowner could use to interview and evaluate contractors, such as “How soon can you begin?” and “How quickly will my work be completed?”

- The Town of Bedford’s Energize New York program learned that selecting a contractor was the primary barrier for homeowners interested in home performance upgrades. The program addressed this challenge by developing a rating system to differentiate high- and low-performing contractors. Contractors’ ratings were calculated using a combination of customer survey results, the number of BPI certifications held by their technicians, and their number of completed upgrade projects. Some contractors were dissatisfied when they received low ratings, and in follow-up discussions, program staff reminded contractors that they would have an opportunity for their score to be updated quarterly and reviewed the scoring criteria. As a result, many of those contractors decided to improve their overall score. The program also set a minimum standard of completed projects (i.e., six completed projects over the last four quarters) for contractors to be included in the program. This narrowing of available contractors made it much easier for customers to select one without being overwhelmed.

- Seattle’s Community Power Works began matching homeowners one-on-one with certified contractors to create the best fit based on homeowner needs, contractor skills, and contractor availability. The program found that its past approach of suggesting two or three contractors led to indecision and that the potential price advantage of competition among these contractors was not an important factor in homeowner satisfaction.

- Programs should be transparent about the process of matching individual contractors to customers and ensure that all qualified contractors have the chance to participate in the program by competing for upgrade projects.

- While Community Power Works did not encounter any issues, programs should recognize that this approach can limit competition among contractors and discourage the growth of new contractors in the market. Most programs, including Enhabit, Austin Energy, Energy Impact Illinois, and many others, mitigate this by allowing contractors who bring their own customers to the program to keep them, providing an incentive for the contractor to market themselves instead of relying on the program to generate demand.

Even with the best contractor partners, a program may sometimes encounter difficulties that require remediation. Consistent with Home Performance with ENERGY STAR program principles, many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners discovered that they could address these difficulties by establishing contractor requirements to set standards for quality work, a transparent remediation process, and measures for dismissing underperforming contractors. They found that the key is to make contractor requirements clear from the beginning of your program. Contractor participation agreements and codes of conduct for interactions with customers can help ensure understanding of standards and provide a rule of thumb for when issues needed to be addressed. Not all contractors are equally skilled or customer-service oriented. These programs learned that, in order to preserve their reputation, they needed to be able to confidently recommend any contractor on their list. It is important to apply corrective actions as needed in response to problems and deficiencies, as well as a procedure to respond to serious or recurring problems such as probation or dismissal from the program. By setting the bar high and dismissing contractors that failed to meet program requirements, these programs helped ensure consistent, quality customer service.

- Efficiency Maine developed a Contractor Code of Conduct that contractors sign, stating that they will respect the homeowner’s property, minimize disruption to the homeowner, and leave the home in as good or better condition as it was found. It lists 15 things that contractors will and will not do relating to communications, onsite behavior, and work practices. To assure quality in the program, a minimum of 15% of upgrade projects are subject to random and/or targeted onsite inspections, covering the pre-installation, installation, and post-installation phases. Efficiency Maine’s Program Manual outlines clear procedures that program staff will follow in the event that the inspections reveal errors, omissions, or inconsistencies. The manual also outlines procedures for removing a contractor from the program’s registered vendor list for repeated failure to correct deficiencies.

- Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska’s reEnergize Program furnished its contractors with an Energy Upgrade Contractor Protocol and General Scope of Work, which governs contractor work processes and customer interactions. This protocol was intended to serve as a supplement to contractors' technical training. It provided rules that contractors were required to follow to achieve customer satisfaction throughout the upgrade process and also outlined basic safety requirements. Topics covered everything from how to greet the customer to cleanup steps once the upgrade was completed. The protocol was an important tool for ensuring that all homeowners had a pleasant experience with the program through their interactions with contractors. It helped the program achieve over 1,300 residential energy upgrades over a 3 year period that included program launch.

- The Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance Better Buildings Chapel Hill WISE program in North Carolina discovered that even though contractors might have met the required program criteria and had qualifying credentials, the quality of their work and their understanding of building science varied substantially. To address these issues, Chapel Hill engaged an external training partner that worked with contractors on the quality of their work and the implementation of quality control mechanisms to improve future work. The program developed and implemented a contractor probationary and debarment policy and corrective action plan. Under that plan, contractors were subject to a corrective process that included a preliminary review of concerns, probation, specific requirements to return to the pre-qualified list after probation, and dismissal from the program. This policy helped the program systematically approach the issue of alerting contractors whose work fell short of the program’s quality standards, and to dismiss contractors who were unable to improve the quality and consistency of their work.

Effective home performance contractors require many types of skills and expertise. To help individuals develop those skills, programs can target training on the specific topics and skills needed for successful home performance work. Many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners found that they could cost-effectively increase their contractors’ access to training by engaging with expert partners to provide training, mentoring, and apprenticeship opportunities. A comprehensive evaluation of over 140 programs across the United States found that the more successful programs offered multiple training opportunities to contractors, either by delivering training or engaging partners to deliver training. By providing access to training, programs saw enhanced assessment quality, more effective sales approaches, increased rates of conversion from assessment to upgrade, more comprehensive upgrades, more effective and efficient installation processes, improved quality control, and increased revenues for contractors.

Training alone does not create jobs in the community, but you can increase the relevance of your training by using contractor input to select training topics. Several Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners found that asking contractors what topics would be valuable also helped the program build an engaged and capable workforce. By providing access to the specific training that contractors want, programs can increase their chances of success by ensuring that they have a strong pool of contractors with a deep understanding of building sciences and the ability to install or subcontract a variety of energy-saving measures.

Some programs found success in working with education and training providers, such as community colleges, universities, and weatherization training centers, to offer valuable and appropriate training to their contractors. Apprenticeships, which can be a bridge between classroom training and being hired by contractors, helped some programs ensure that students acquired the skills that employers want. These programs also found that accredited, on-the-job training can be a relevant, less expensive, and more motivating supplement to classroom training.

- Community Power Works in Seattle piloted a new training approach to meet contractor needs and the requirements of the city’s high-road workforce agreement. The program’s original training programs relied on an outdated model of training, failed to prepare technicians properly to be hired, and lacked adequate mentorship and job-finding support for training graduates. The new approach included partnering with South Seattle Community College and the nonprofit Northwest EcoBuilding Guild, which offered classes and workshops, as well as participation by contractors to gather their feedback on training options. Training was available to both entry-level and experienced home performance professionals, and contractors were given the flexibility to hire first and train second (e.g., hire a technician who is not fully trained or certified but can begin or is in the process of completing certifications). In this way, the contractor could select from a wider pool of candidates and then provide supplemental training to those who need it. The training was fully subsidized by the program. By establishing these ongoing collaborative partnerships with contractors, Community Power Works helped to ensure that it has a robust workforce of trained professionals for the future. As a result of these partnerships, about 40 training graduates have worked around 23,000 hours on Community Power Works projects between April 2011 and December 2013.

- Philadelphia’s Energy Coordinating Agency collaborated with the Community College of Philadelphia to design an apprenticeship program for energy efficiency and building science. Two one-year programs—“Building Energy Analyst” and “Weatherization Installer and Technician”—led to journeyman credentials and BPI certification. These programs trained home performance professionals with the technical building science skills they needed, while also providing hands-on experience with energy efficiency analysis and installation of energy efficiency measures. Program trainees helped residents save an average of 20% to 30% on utility bills through weatherization and energy conservation services.

- Austin Energy emphasized making its contractor training locally relevant. The program encouraged trainers to highlight issues that were particularly applicable to the local climate and housing stock, and to focus on regionally-appropriate amendments to energy code. For example, basements are uncommon in Austin houses, so training should avoid seeming out of touch and refrain from discussing basement upgrades. The program also learned that trainers should allow time for participating contractors to raise issues and questions that are specific to their geographic area and most pertinent to the local community in which they work.

- EnergyWorks Kansas City’s program implementer, Metropolitan Energy Center (MEC), provided training and mentoring for home energy professionals, including training for BPI certification. Training courses included residential and commercial energy assessment, healthy homes, and deconstruction. One training session focused specifically on small and women-owned businesses. To follow up on the training, MEC instituted a mentored practicum experience in which each student was required to complete a full complement of diagnostic tests with the instructor in a dummy house. EnergyWorks Kansas City and MEC also worked with seasoned contractors to provide mentoring to newer contractors in the program. From 2011 to 2014, 90 individuals participated in MEC’s introductory home performance training program. The training and mentoring program allowed new technicians to enter the home performance market: from 2009 to 2014, the number of certified residential auditors in Kansas City increased from six to over fifty, almost all of whom have received training from MEC.

Resources

The following resources provide topical information related to this handbook. The resources include a variety of information ranging from case studies and examples to presentations and webcasts. The U.S. Department of Energy does not endorse these materials.

To deliver the most effective residential energy efficiency programs possible, NYSERDA implemented a quality assurance process to verify that projects meet all program requirements while maintaining healthy and safe conditions for the occupants.

This summary from a Better Buildings Residential Network peer exchange call focused on implementing process improvements using lean processes, an approach of continuous improvement, use of Standardized Workforce Specifications (SWS) to improve quality, and contractor feedback tools. It features speakers from DOE, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), and Arizona Home Performance.

This summary from a Better Buildings Residential Network peer exchange call focused on quality assurance of energy efficiency services.

This presentation provides guidance to contractors on business fundamentals, marketing and lead generation, successful consultative selling and closing, and measuring and improving performance.

This guide assists with developing an implementation plan for a Home Performance with ENERGY STAR program. It covers key elements of the plan, including the scope and objectives of the program and the policies and procedures that will ensure its success, including co-marketing and brand guidelines (section 1), workforce development and contractor engagement (section 3), assessment and report requirements (section 4), installation specifications and test-out procedures (section 5), and quality assurance (section 6).

This publication includes best practices for how to create a quality assurance plan and the key components that these plans should include.

The Residential Retrofit Program Design Guide focuses on the key elements and design characteristics of building and maintaining a successful residential energy upgrade program. The material is presented as a guide for program design and planning from start to finish, laid out in chronological order of program development.