Description

Continuous improvement is the internal, ongoing, and informal process that organizations undertake to address challenges and improve their performance over time. It is also known as organizational assessment. Continuous improvement is distinct from process evaluation, which is a formal assessment of performance (often at the program level), typically conducted by a third party at a specific point in time.

Assessing and improving organizational processes is a critical part of ensuring the viability of an organization and the energy efficiency services it provides. Organizational improvements include streamlining decision-making processes, establishing better accounting and invoicing procedures, aligning staff and other resources with areas of critical need, and updating your business model.

Continuous improvement at the organizational level is informed, in part, by data collection efforts described in the Market Position handbook on developing evaluation plans, but is also informed by data tracking, ongoing feedback from key stakeholders, and periodic checks against organizational vision, mission, and goals. The key to improving the effectiveness of an organization offering energy efficiency services is evaluating and analyzing data sets, which will help diagnose organizational strengths and weaknesses.

This handbook describes how to implement a continuous improvement process and establish key performance indicators. This includes ways to identify areas for improvement, such as revisiting your organization’s market assessment and comparing your organization’s current performance to your past performance and the results for other similar organizations (i.e., benchmarking). It also includes details on how you can prioritize issues to be addressed and identify steps for implementing changes inside your organization.

Specifically, you will learn how to:

- Track and collect data on your organization’s performance

- Review and assess the data you have collected

- Make decisions and implement solutions based on your data analysis

- Regularly review and re-evaluate your data to ensure continuous improvement.

Step by Step

The steps below describe how you can assess and improve your organization’s performance over time, laying the necessary groundwork for delivering a successful residential energy efficiency program. This assessment is important for a number of reasons, including allowing you to:

- Identify underlying operational issues and apply effective solutions to address them

- Respond to changes in the marketplace

- Smoothly transition to new management, if needed

- Ensure that thriving programs are sustained by pinpointing what is working well at the organizational level.

As noted in the Market Position handbook on developing evaluation plans, you should regularly consider whether the management systems and processes that you have established for your business are performing as expected.

To help you understand how well your organization is operating, you should establish key performance indicators (KPIs). These are essentially metrics of success that you can easily track over time and provide meaningful information with which you can better measure your organization’s performance.

Organizations track many types of KPIs. Tying your KPIs to the steps in your evaluation plan will streamline data collection activities and ensure that there are strong ties between the planning and implementation of your organization’s evaluation activities. Example KPIs can include those related to:

- Market position

- Percentage of home energy upgrades conducted/completed by your organization (market share) in any geographical area

- Web-based measures such as search engine ranking and click-through rate

- Vision, mission, and goals

- Your employees’ understanding of the vision, mission, and goals (e.g. do you provide “on-board” training on this to staff at all levels?)

- Milestone attainment for semi-annual, quarterly, or annual goals (e.g., are you on track to meet each of your established goals?)

- Number of services or programs aligned with core values, goals, and objectives

- Regular reviews of your goals and objectives in the context of competition and changes in the marketplace

- Business operations

- Average indirect costs (i.e., marketing, HR, and overhead) per energy assessment and upgrade

- Average indirect costs as a percent of total revenue

- Number of days of cash on hand

- Number of unique website visitors

- Average employee tenure

The best KPIs are tied to your organization’s business model and reflect your position on the business life cycle.

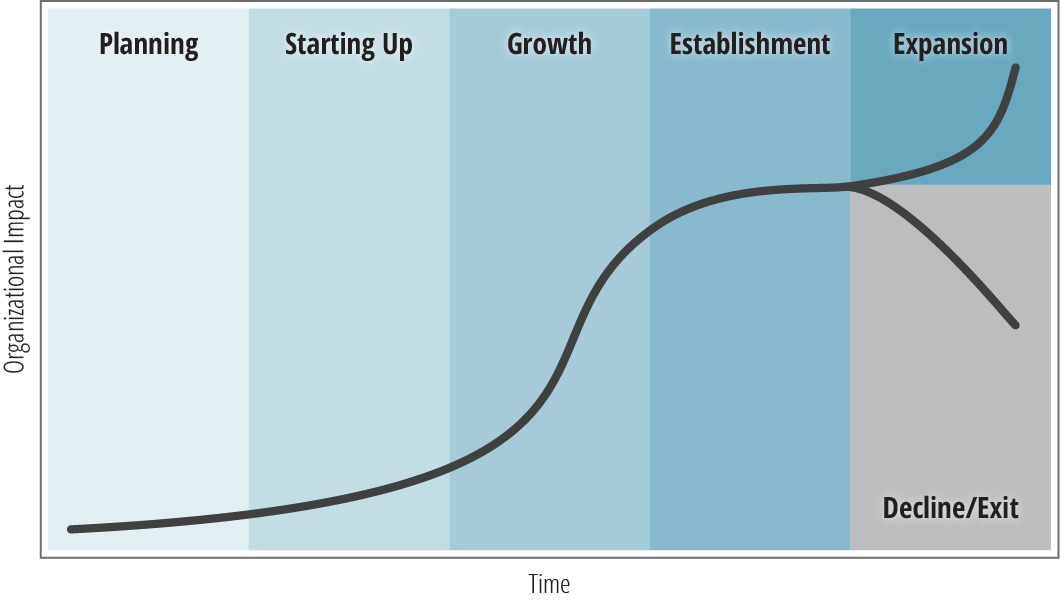

Phases of a Business Life Cycle

For example, if you are planning for your organization’s launch, your KPIs may largely revolve around securing funding (e.g., a list of stakeholder/funders to reach out to, understanding of their capacity to provide you with funding, the number of committed funders and the status of the total funding received to date). On the other hand, if you are in the expansion phase, your key indicators may include the number of days it takes you to hire and train new staff, the number of customer requests and/or complaints, and the time to act on those requests/complaints.

KPIs often remain the same as your organization progresses through the life cycle stages, but the target performance level may change. For example, the number of unique website visitors is one of the KPIs common to many organizations. The target may start out low when your organization launches, but as you establish a wider presence in the marketplace, that target should change. Regardless of your organization’s size, number of website visitors may be a KPI to track over time in order to evaluate your online presence and market position. Evaluating and adjusting your targets to fit where your organization is in its lifecycle will help you meet your stated goals and vision.

Once you have collected data on each of your KPIs, review and understand the data to identify what areas might need attention or a change in organizational processes. One way to assess your data is by benchmarking. The two types of benchmarking explained in this step—internal and external—will:

- Help identify where the organization is over- or underperforming

- Help you determine if you need to refine your vision, mission, and goals to reflect the current environment

- Allow you to communicate progress or failures

- Enable you to assess where there are opportunities for improvement and develop a process for implementing changes

- Support justification of a renewed investment in your organization.

Internal Benchmarking

Internal benchmarking involves comparing your current KPIs to your own organization’s performance in the past, as described in the example below. You can also internally benchmark by comparing your current KPIs to your projections or proformas. See the National Home Performance Council’s draft contractor proforma tool for example measures.

Example: Benchmarking against Your Past Performance

Using the number of days it takes you to process contractor incentive payments as your KPI, assume that on average over the past 12 months, it has taken your organization 21 days to complete that process. That would mean that from the time a contractor applies for an incentive, it takes your organization three weeks to verify that the work was done, process all of the paperwork, and cut and mail a check. If you compare your past month’s performance to that rolling 12-month average, you may find that the number of days has reduced to 17.

Analyze why this is the case. Perhaps you hired a new administrative assistant to work on that process. If that is the reason, it shows that your operations are improving. On the other hand, perhaps the sheer number of contractor incentives has decreased significantly over the past two months, meaning that your staff has less work to do. This explanation points to other improvements that need to be made. In either case, it is important to diagnose the root cause of any changes in performance.

External Benchmarking

External benchmarking involves comparing your organization's results with an external peer group, (i.e., a group of organizations similar to yours). Given the low likelihood that you will find another organization structured and managed in exactly the same way in exactly the same external environment, you will want to compare your organization to others that operate similarly to you for the specific KPIs you have established. For example, when benchmarking your KPIs related to your business model, you will want to compare yourself to organizations whose business models very closely match your own, regardless of their visions, missions, and goals.

Example: Benchmarking against External Peer Groups

If it typically takes you 21 days to pay contractor incentives and it takes another organization 12, you may conclude that your operations and processes are lagging behind your peers. A closer examination, however, may show that the organization that you are comparing yourself to has a budget three times the size of yours and four more administrative staff who process payments. This organization and your own are like apples and oranges. You should seek to compare your performance to that of similarly sized and staffed organizations, with similar organizational structures and management approaches.

If you need help identifying peers for benchmarking, the Better Buildings Residential Network offers multiple opportunities for doing so, including through monthly peer exchange calls on topics related to residential energy efficiency programs and an online discussion forum.

U.S. Department of Energy’s Program Benchmarking Guide

The U.S. Department of Energy developed a guide for benchmarking residential energy efficiency program progress. The guide lays out an action plan for developing an internal Benchmarking Plan for your residential program. A complementary presentation provides an overview of the guide.

Depending on your current operations, you may not need to implement all of these steps, but consider each of them when developing your own benchmarking plan.

- Step 1. Use Program Goals to Guide Benchmark Planning

- Step 2. Identify Potential Metrics that Measure Your Goals

- Step 3. Determine How You Will Collect the Information

- Step 4. Assess Level of Effort and Finalize Metrics

- Step 5. Put the Process in Place and Get Started!

- Step 6. Share Results Effectively

- Step 7. Consider Benchmarking Against Peer Programs

Once you have a peer group identified, you should explore whether they are willing to share information with you about their performance. Many organizations are interested in sharing these details so that they can improve their own outcomes, particularly if operating in non-competitive markets. You should discuss with your peers what information would be most useful to share, drawing on the list of KPIs you developed in the previous step.

When comparing your results to your peers, look for areas in which you are outside the norm. When your performance is lacking, ask whether there are any changes or best practices in organizational operations that you can adopt. At the end of this step, you should have a list of the areas in which your organization’s performance is either declining or is not on par with that of your peer group. This list will help you as you move into the next step.

Example: Identifying Opportunities for Process Improvements

Comparing your 21-day contractor payment timeline to your peer group, you find that your organization takes seven days longer than they do on average. This indicates an opportunity for process improvement. You also find that two of your peers have implemented a large-scale software-based financial management system that automates payments, that two others have recently reworked their existing payment processes to enable administrative staff to respond more quickly, and that another has improved its cash flow position by opening a line of credit at a local bank to enable timely payments to contractors.

To prioritize how you spend your time, begin with the list of areas for organizational improvements you generated in the previous step. Of the items on that list, determine which have the largest variation from the norm (either your own past performance or your peer group’s performance) or are farthest from where they need to be to enable your success (i.e., deviation from your goals). This list should be your starting point, as it represents your greatest opportunities to improve.

Next, for each priority, you should brainstorm steps to improve processes for better performance. During the brainstorming exercise, list all options and try to generate as many ideas as possible.

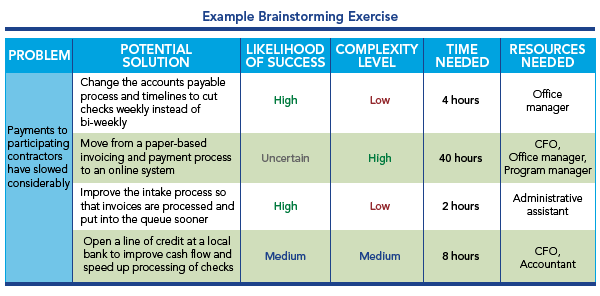

To refine your brainstormed list, indicate the level of complexity, time, and resources (or any criteria you deem appropriate) required for each action, as well as the likelihood of success. Note that when it comes to time, it is better to overestimate and be wrong then to underestimate; the amount of time it takes to complete activities can often be much longer than expected. This will help you rank the actions you should take. Capturing this information in a table may be a good way to compare and identify potential solutions. Prioritize actions that have a high likelihood of improving your organization performance, low complexity, and low time needed.

Carrying forward the previous step’s example about contractor incentive payment timelines, an example of this brainstorming exercise is provided in the table below.

You can use a matrix like the one shown above to identify the process improvements that make the most sense for your organization, based on available resources and anticipated outlook.

The best solution or option, however, may not yet be clear or known. This can leave you with several options.

- Consider piloting a potential solution for a small period of time, reassess how it affects your organization’s performance, and then decide whether to implement it more broadly or put it aside and move on to the next option.

- Another option is to reach out through your peer network for more information, lessons learned, or expert opinions before implementing a specific approach. Bringing in outside expertise can be particularly helpful.

Example: Gathering Peer Insight to Define Solutions

Continuing with the contractor payment timeline example used throughout this handbook, if you have trouble deciding which step to take, you can speak with a member of your peer group about each potential solution. You can ask which approaches they have tried in the past, what the results have been, and whether they have any recommendations for you. Through this discussion, you might realize that the contractor training and the improvements to your invoice intake process are most likely to yield the desired result in your situation.

Regularly review and re-evaluate your performance (e.g., monthly or quarterly) to help you understand the effect of management decisions on the organization’s performance and the impacts of process improvements.

After you have established KPIs and developed the system for tracking these important metrics of business success, reviewing your results is a good, efficient way to become aware of performance issues early and address them proactively. This will allow you to continually deliver critical information about your organization’s fundamental strengths and challenges to decision makers (e.g., boards) and external stakeholders (e.g., potential partners and funders) and point you to necessary improvements.

Making changes known to all the employees and having all levels of organizational structure appropriately use and apply any improved processes is the first step in ensuring long-term, operational excellence. It may also make sense to translate your KPIs to evaluation metrics for your employees. If they know they will be at least partially rated on if (or how well) they implement the KPIs, they are more likely to do so, and thus, the changes you identified are more likely to stick. You must also support organizational changes with effective communication, necessary training, and appropriate tracking and documentation in order to see if the changes implemented are sufficient to address the issues identified and have the intended effects. If not, you can revisit your options and revise your approach until you find one that works.

Tips for Success

In recent years, hundreds of communities have been working to promote home energy upgrades through programs such as the Better Buildings Neighborhood Program, Home Performance with ENERGY STAR, utility-sponsored programs, and others. The following tips present the top lessons these programs want to share related to this handbook. This list is not exhaustive.

To develop a successful business model, Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners found it critical to have a strong understanding of the external environment within which they operated. This included who their customers were, who their competitors and partners were, what key policies governed their work, and what trends were likely to impact their ability to accomplish their goals and fulfill their mission. Understanding the external forces that affected their market allowed the organizations to better identify services that met customers’ and partners’ needs and develop a more robust business model. Many organizations adapted their business model to overcome challenges and leverage opportunities as local conditions and their understanding of how their business operated within the market evolved.

- When the New Hampshire Better Buildings program began, there were numerous energy efficiency programs operating independently in the state (e.g., by multiple utilities), and only informal coordination among activities was occurring. Customers were often overwhelmed trying to determine which programs they qualified for, how to fill out all the required paperwork, and which contractors they were able to work with. The program quickly learned that their business model needed to be well-integrated with other energy efficiency programs in the state, in order to provide value to customers and contractors while enabling long term growth for the efficiency market.

In response, the program took a collaborative approach to their business model design and partnered with the utilities’ rate-payer funded Home Performance with ENERGY STAR (HPwES) program. Combining programs leveraged the utility programs’ existing queue of upgrade projects, procedure for assessments and upgrades, and database for collecting information about each project. A single program and process also made the most sense for residential customers, who were more likely to move forward with a project if they did not have multiple programs and processes to figure out. The utility companies benefitted from the partnership because the additional funds from Better Buildings allowed them to expand their program’s reach. Combining efforts and utilizing each program’s strengths led to consistent marketing and messaging, more efficient processes for contractors, one-stop shopping for customers, and a streamlined approach to financing.

- The Neighbor to Neighbor Energy Challenge’s (N2N) original program design used community-based social marketing (CBSM) to acquire and feed leads into the existing ratepayer funded Home Energy Solutions (HES) assessment program. N2N expected that contractors would convince customers to take advantage of rebate programs to complete home energy upgrades; however, over the first two years of the program, they saw many of the leads they generated stall after the assessments. N2N realized that they had limited influence over the contractor network with this approach and that the HES program design did not incent contractors and customers to complete upgrades. They shifted their business model and focused marketing and outreach resources on new strategies, such as direct lead acquisition, in order to acquire customers who were more likely to proceed straight to completing upgrades.

In order to craft a sustainable financial model, organizations need to identify long-term sustainable revenue sources. As with the Better Buildings Neighborhood Program, grant funding can be a great way to get an effort off the ground; however, grant funding does run out, leaving the need to secure alternate revenue sources. Many Better Buildings Neighborhood Program partners overcame this challenge by aligning revenue opportunities with gaps or untapped potential for business in their local market. In some cases, several years were needed to gain trust and demonstrate results before funding was secured, so the sooner you begin considering options, the better the chances are of finding and securing one that is viable. Consider a wide range of options and pursue those opportunities that best match what your organization and local market have to offer. See a detailed list of potential funding sources in the Market Position - Develop a Business Model handbook.

- In 2010, St. Lucie County in Florida was awarded an Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant and created the Solar and Energy Loan Fund (SELF), expecting that property assessed clean energy loans (PACE) would be an integral part of the residential loan structure. When Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae challenged the residential PACE system nationwide, SELF shifted direction. They evolved through a multi-year process into a certified community development financial institution (CDFI) focused on energy efficiency and renewable energy upgrades for the residential sector. They targeted low and moderate income populations that had been especially affected in Florida by the economic crisis in 2009.

- The change meant that SELF no longer had access to capital from investors seeking highly secured and profitable investments through PACE; however, becoming a CDFI allowed SELF to diversify its products and receive new types of support in the form of grants for technical assistance and loan capital. By becoming a certified CDFI, SELF was able to attract capital from banks as Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) investments and establish legitimacy in the eyes of other socially responsible investors. For example, in the last year of operating under the Better Buildings grant, SELF contacted faith-based foundations that seek to make socially responsible community investments. Over the year and a half after the Better Buildings grant, SELF raised an additional $835,000 from 5 different religious organizations.

- Under their business model, SELF faced some challenges limiting their ability to attract capital. For example, even though they implemented new policies to have Uniform Commercial Codes and a more strict collections process, capital providers are still wary of the fact they provide “unsecured” loans. Nevertheless, SELF’s portfolio results of less than 1% default and less than 3% delinquency helped prove that they had a good evaluation method and their risk management procedures were effective. The new CDFI business model allowed SELF to become self-sufficient by providing a platform to offer financial and non-financial services that could generate diversified revenue streams. These revenue sources include interest and fees earned on their investments; fees from off balance sheet portfolios such as commercial PACE; and fees from partnering with other financial institutions to sell their financial product and other activities such as contractor training.

Resources

The following resources provide topical information related to this handbook. The resources include a variety of information ranging from case studies and examples to presentations and webcasts. The U.S. Department of Energy does not endorse these materials.

This case study of Arizona Public Service (APS) and Arizona’s HPwES Sponsor, FSL Home Energy Solutions (FSL), focuses on their continuous improvements designed to elevate customer and contractor experience while boosting program cost-effectiveness.

What's Working in Residential Energy Efficiency Upgrade Programs: Greater Cincinnati Energy Alliance

This summary from a Better Buildings Residential Network peer exchange call focused on implementing process improvements using lean processes, an approach of continuous improvement, use of Standardized Workforce Specifications (SWS) to improve quality, and contractor feedback tools. It features speakers from DOE, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), and Arizona Home Performance.

Achieving energy savings goals and improving customer and contractor satisfaction while staying cost-effective makes managing home energy upgrade programs challenging. DOE's Home Upgrade Program Accelerator is working with program administrators to identify strategies that overcome challenges and achieve better results. The Arizona Home Performance with ENERGY STAR program completed process improvements that improved contractor satisfaction and deceased quality assurance labor. Build It Green implemented software improvements to their utility program's online rebate applications portal to accelerate data processing.

This guide provides recommended benchmarking metrics for measuring residential program performance.

Tool to evaluate contractor impacts on program revenue.

The Best Practices Self-Benchmarking Tool can be used to identify in your own programs their strengths, areas of improvement needed, and strategies for improving them, based on the results of the Best Practices Study.

Keeping Up With Your Audience, So They Keep Up With Your Program

This report serves as a resource for program administrators and building contractors who are or may be interested in starting or expanding their services into the residential energy efficiency market.

The Residential Retrofit Program Design Guide focuses on the key elements and design characteristics of building and maintaining a successful residential energy upgrade program. The material is presented as a guide for program design and planning from start to finish, laid out in chronological order of program development.